How objective is the war photographer?

The camera can’t lie but the camera always lies, this is the strange thing about photography the camera itself is a recording instrument and in itself does not alter the truth of an image however the photographer behind the camera has every chance and possibility to choose when, where and how to use his camera thus altering the truth of the final image. It can be even further re-contextualised with placement and captioning, more on that issue later. Any choice a photographer makes in capturing any particular event will clearly affect the content and hence the truth of the final image. The choices of where he or she points the camera and exactly what to include in the frame may depend on what the circumstances allow, for instance any photo journalist working under a live fire situation will be more than likely highly stressed, unable to choose their camera position with the normal luxury of time and safety usually enjoyed by general photographers.Maybe more important than considering what to include is actually what to exclude from the frame, part of the story excluded might give a different interpretation of the final image which is the pertinent point in the controversial photograph below.

The staging of war photographs goes way back to Roger Fenton’s two near identical images taken in 1855 in the famous Valley of Death, where the famous disastrous charge of the light brigade occurred The 2 images are nearly identical but one has a proliferation of cannon balls strewn across the ground. Do we think someone removed the cannon balls to make a neater image? Hardly likely especially as Fenton was employed by British publishers, Thomas Agnew and Son, to produce images to compile a book to sell to a Victorian England to be a ‘testimony to the rigours of war’ (ref). Whilst not the actual first war to be photographed, the American war with Mexico 1846-46 war had been covered by a few Daguerreotypes, Roger Fenton’s Crimean coverage was very professional and provided over 350 iconic images of scenes that had never been seen by the public before. As the photographic process of the time necessitated exposure times of 15 seconds or more scenes are all very static, staged posed shots, soldiers at rest or mounted on horses with some impressive uniforms. Not only was action beyond his means but he was also told not to show the suffering and disease ridden army.

Fenton’s image of the Valley of death (as coined by Tennyson in his famous poem) is a portrait of Absence, of death without the dead. Sontag.s (2002

In a letter to his wife Fenton simply writes that ‘today I made 2 excellent images.’ not referencing anything else, however, as Fenton arrived in the Crimea six months event this most throw more suspicion on the photograph as cannon balls were a very useful commodity and would hardly be left lying around for the enemy to retrieve if they had done so already themselves.

Letters: Roger Fenton’s Letters from the Crimea (s.d.) At: http://rogerfenton.dmu.ac.uk/showLetter.php?letterNo=1 (Accessed 28/11/2020).

“Fenton was financed by Thomas Agnew and Sons of Manchester who wanted to produce an album suitable for sale to a Victorian audience. His photographs are not an accurate record of the war. He was instructed not to record the horrors of war and his photos are therefore carefully constructed images designed to emphasise certain aspects of the conflict that would be agreeable. The technology available ruled out action photographs – exposure times were very long and seems therefore needed to be static”

Ponting, C. (2011) The Crimean War: The Truth Behind the Myth. (s.l.): Random House. page XI (25th November 2020)

It is worth noting that other photographers were commissioned, by the Britsh army itself, one never made it to the Crimea and presumably drowned in a storm on the way to Balaclava. A pair of photographers working together did capture other plates but they were deemed of low value and subsequently disappeared. Although Roger Fenton was not commissioned by the army, but a publishing house, his letter of introduction from Prince Albert was more than sufficient to allow him to work with the army. Roger Fenton’s images stand alone as a superbly crafted photographic testimony to the conflict.

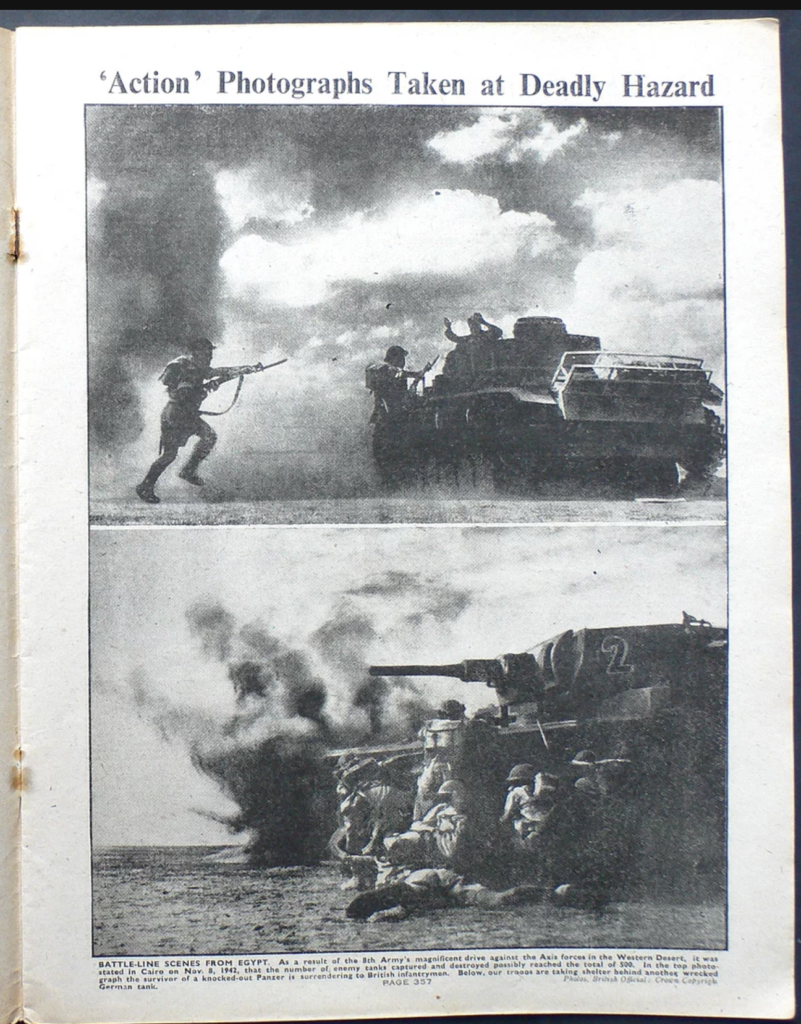

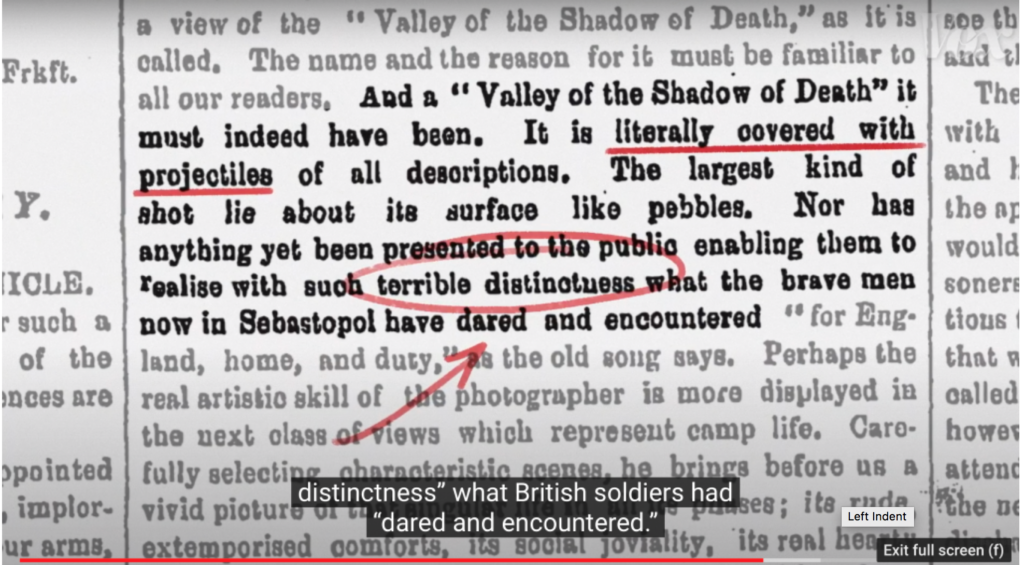

A very relevant point is made here in a Times newspaper article dated 20th September 1855. I apologise for the screen grabs I am trying to source a digital copy via the British Library but the reading room is shut due to COVID-19 and the UH Library did try to get the relevant copy through the library sharing scheme but were unable to find the exact one, only similar Crimean articles

The article states ‘And a valley of the shadow of death it must have been. It is literally covered projectiles of all descriptions. The largest kind of shot lie about it’s surface like pebbles. Nor has anything yet been presented to the public enabling them to realise with such terrible distinctness what a brave man now in Sebastopol dead and encoutered.’

Times newspaper (1855) Art. Opinions of the press. Referenced by Errol Morris in YouTube video. (Accessed 21st November 2020)

Paintings

There is a big contrast to paintings of the conflict, war artists were sent to cover the campaign and create iconic imagery depicting the glorious British army victories. They were able to represent the action and drama missing from the static photographic representations, and of course with a highly romanticised portrayal such as the image below.

‘Death or Glory‘. Is the motto of the British 17th Lancers featured in the fore of the above painting of the infamous charge of the Light Brigade.

Crimean War | National Army Museum (s.d.) At: https://www.nam.ac.uk/explore/crimean-war (Accessed 26/11/2020).

American civil war

The American Civil war was photographed by Mathew Brady and his self financed team of photographers. One of which was Gardner who captured the photograph titled ‘Home of the rebel sharpshooter’. However there is conjecture that body was repositioned as well as the Rifle propped in the shot would not have been the type used by a sharpshooter (the term ‘sniper’ is a relatively modern hunting term and comes from the Snipe bird being notoriously difficult to shot in flight) would not have been the sharpshooter’s rifle, but Gardner I didn’t know or care.

Further deliberate re-stagings are famous, including the famous image of the Stars and Stripes being raised on Iowa Jima in the second world war. Do these photographers have no disregard for truth! Even Dorothy Lange’s iconic image of the migrant worker and her family, although not war related, has been doctored with a thumb mysteriously retouched from it. Does this change our interpretation of the image? That will depend on the viewer and their particular sensibilities, but never the less the image has been manipulated with the assumed purpose of affecting the photograph’s perceived meaning. I will try to evaluate later the reasoning behind these obvious misrepresentations.

A bigger question is to pose is of the possible influence a photographer has on the outcome of a situation by simply being at the scene with a camera.

Who shot the most famous war photograph ever?

This is Robert Capa’s iconic ‘Falling Soldier’ shot. Heralded as the most famous war photograph ever taken, but also surrounded by controversy.

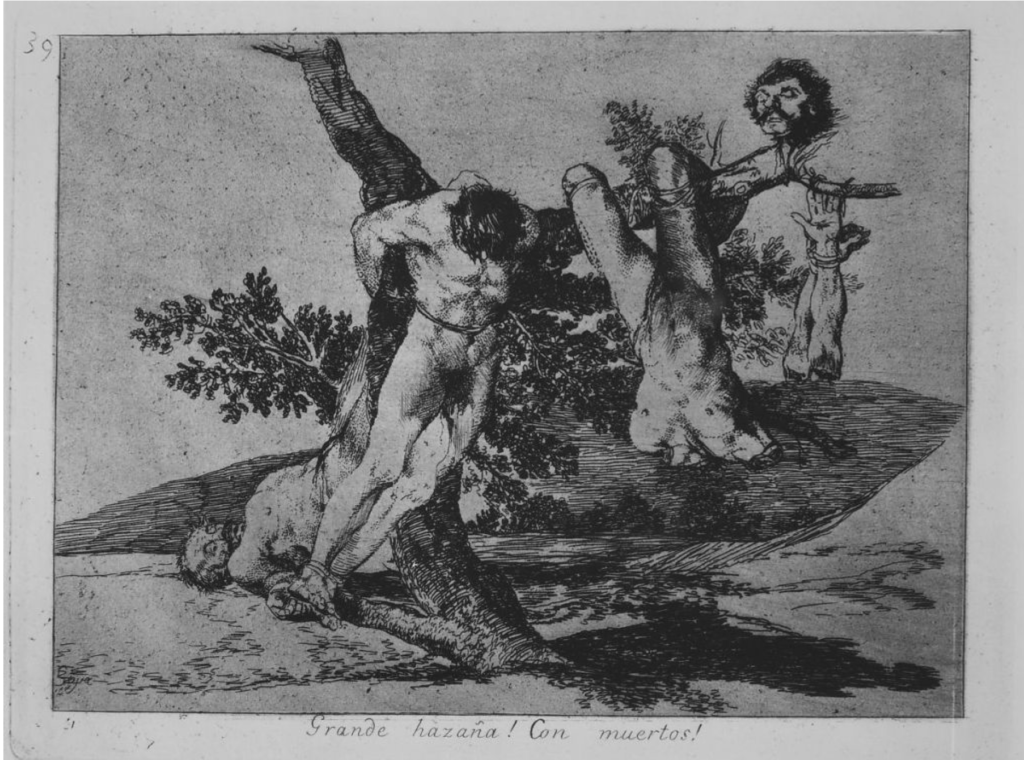

Susan Sontag writes (p40 2002) “ that the atrocities perpetrated by the French soldiers in Spain didn’t happen exactly as pictured – say, that the victims in didn’t look just so, that it didn’t happened next to a tree – hardly disqualifies ‘.The Disasters of War’. Goya’s images are a synthesis. They claim things like this happened in contrast a single photograph or filmstrip claims to represent exactly what was before the camera lens. A photograph is supposed not to invoke but to show. That is why photographs, unlike hand made images can count as evidence. But evidence of what? The suspicion that Capa’s ‘Death of a Republican Soldier’ titled ‘The Falling Soldier’ in the authoritative compilation of Capa’s work – may not show what it is said to show (one hypothesis that it recording training exercise while on the frontline) continues to hold discussions or photography. Everyone is a literalist with comes to photographs’

Sontag.s (s.d) Regarding the pain of others. (p40.2002) Penguin books. Random house. (Accessed 28/11/2020).

She later writes: ‘Walter Lipman wrote in 1922 “Photographs have the kind of authority over imagination today, which the printed word had yesterday, and the spoken word had before that. They seem utterly real’ (p.40)

Goya (Francisco de Goya y Lucientes) | The Disasters of War (Los Desastres de la Guerra), title page (s.d.) At: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/333838 (Accessed 28/11/2020).

‘The Falling Soldier’

How did Capa manage to get such an iconic photograph? Capa talks about shooting the soldiers on a quiet hillside being crazy for the camera while he photographed. Ironically it was the soldiers firing shots for the camera that most likely drew the attention of the enemy guns and caused the soldier’s death. The solder was identified as Federico Borrell Garcia, (Ref. R.Whelan 2003.) decades after the war.

Although this iconic photograph is genuine and made Capa famous, Capa is also shown to have some responsibility in the soldier’s death as has been referenced in this article below.

(Ref. R.Whelan 2003. P.2) “The disturbing fact of the soldier’s flat-footedness, along with the equally disturbing inference that the man was carrying his rifle in a way suggesting that he did not expect to use it soon, led me to reconsider the story that Hansel Mieth, who had become a Life staff pho- tographer in the late 1930s, wrote to me in a letter dated March 19, 1982.

She said that Capa, very upset, had once told her about the situation in which he had made his famous photograph.

“They were fooling around,” he said. “We all were fooling around. We felt good. There was no shooting. They came running down the slope. I ran too and knipsed.”

“Did you tell them to stage an attack?” asked Mieth.

“Hell no. We were all happy. A little crazy, maybe.”

“And then?”

“Then, suddenly it was the real thing. I didn’t hear the firing – not at first.” “Where were you?”

“Out there, a little ahead and to the side of them.”

Beyond that, Capa told Mieth only that the episode haunted him badly. He implied that he felt at least partially responsible for the man’s death – a feeling that he naturally did not wish to make public, and so he altered various details in his several accounts of the circum- stances in which he had made his photograph.”

Whelan, R. (2002) Proving that Roger Capa’s Falling Soldier’ is real’. APERTURE magazine, [Online] no 166. (Spring 2002) [accessed:23rd November 2020]

So this article does suggest that Capa has some responsibility in the soldier’s death. There is another photograph of a soldier dying in almost exactly the same spot. Which is another reason the validity has been doubted, however in Richard Whelan’s book it is suggested that the original soldier had been dragged back into the trench and poor fellow who went recover the rifle then got shot also.

This. presumably later photograph, has very little visual impact compared to the more famous one. However, for me personally I find Capa’s description of how he shot these images to be doubted. In the radio interview below he says he simply put the camera over his head and out of the trench to take the snap blindly. Quite a feat to capture moments like this with a camera requiring manual film advancing. (motor winds are decades away). Let alone have the 2 images so similarly framed.

Capa is said to have altered the truth in his comments to Mieth, so that certainly must put his honesty in question?

Radio interview in 1947. Spanish civil war covered 11 mins 40 second which further suggests Capa twisted the truth

Radio interview in 1947. Spanish civil war covered 12 mins.

It is my opinion that although the image is a genuine death it would not have occurred without Capa’s presence.

There is second controversy concerning Capa’s photography, although certainly not staged, his D-Day images again contain incredible iconic imagery, the most famous is of a soldier lying in the surf of a Normandy beach on June 6th 1944. The image is blurred and grainy and one of only 10 images to survive from a hundred and one ( His words) he took that momentous invasion. He blames the assistant on having the film drying cabinet too hot after development and melting the film emulsion, but with my extensive first hand knowledge of film developing this is very unlikely, if not impossible. He says he was scared but maybe this fear disabled his ability to shoot? I have never seen the missing/damaged 91 frames published which I find suspicious.

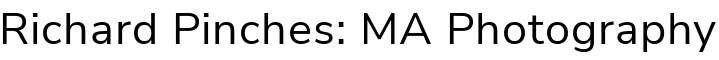

The desert 1942

Now to my favourite war arena , the North African desert in the second world war, because my father was there as a 8th Army desert rat and I grew up with his stories of his time there.

| The Australian War Memorial (s.d.) At: //www.awm.gov.au/collection/042070/ (Accessed 09/11/2020).

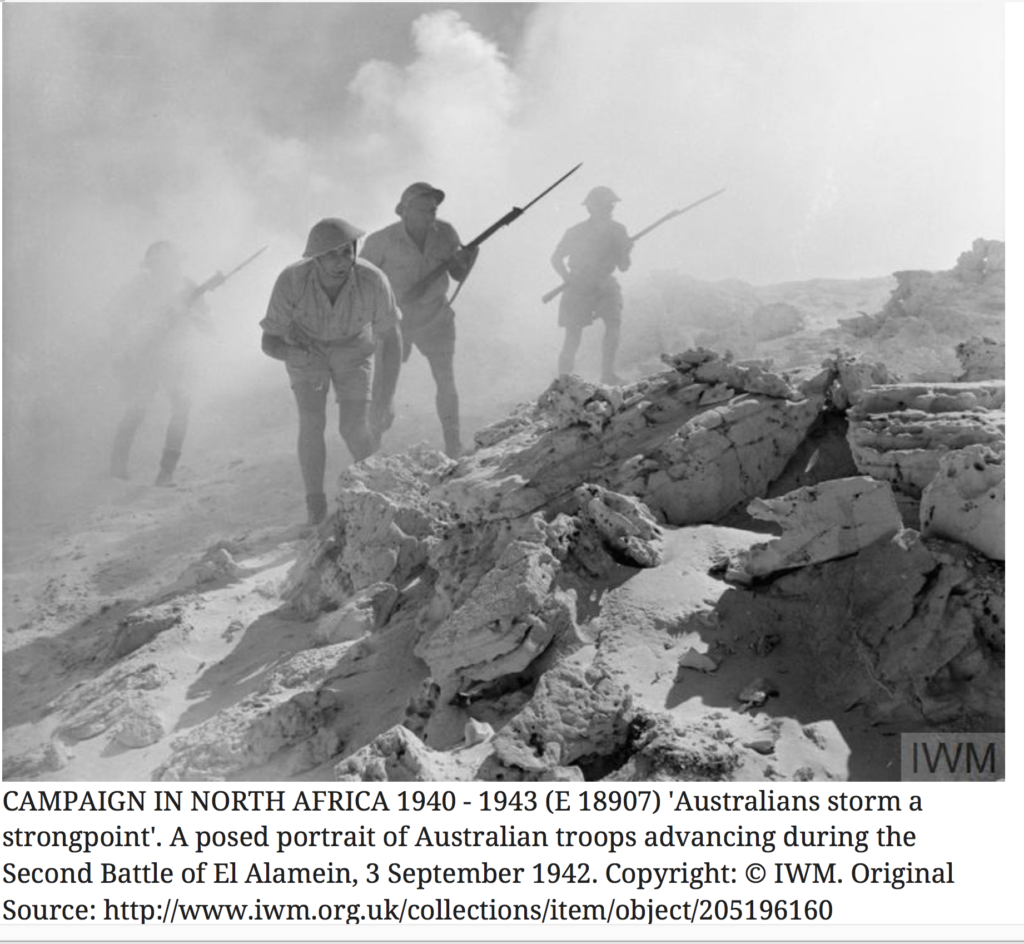

The original caption for this photograph states: “El Alamein sector, Egypt. 3 November 1942. Troops of the 9th Australian Division were being held up by a German strongpoint. They decided to storm it and pave the way for a further advance. Through a dense smoke screen which hid their movements from the enemy, the Australians approached the strongpoint, ready to rush in from different sides.”

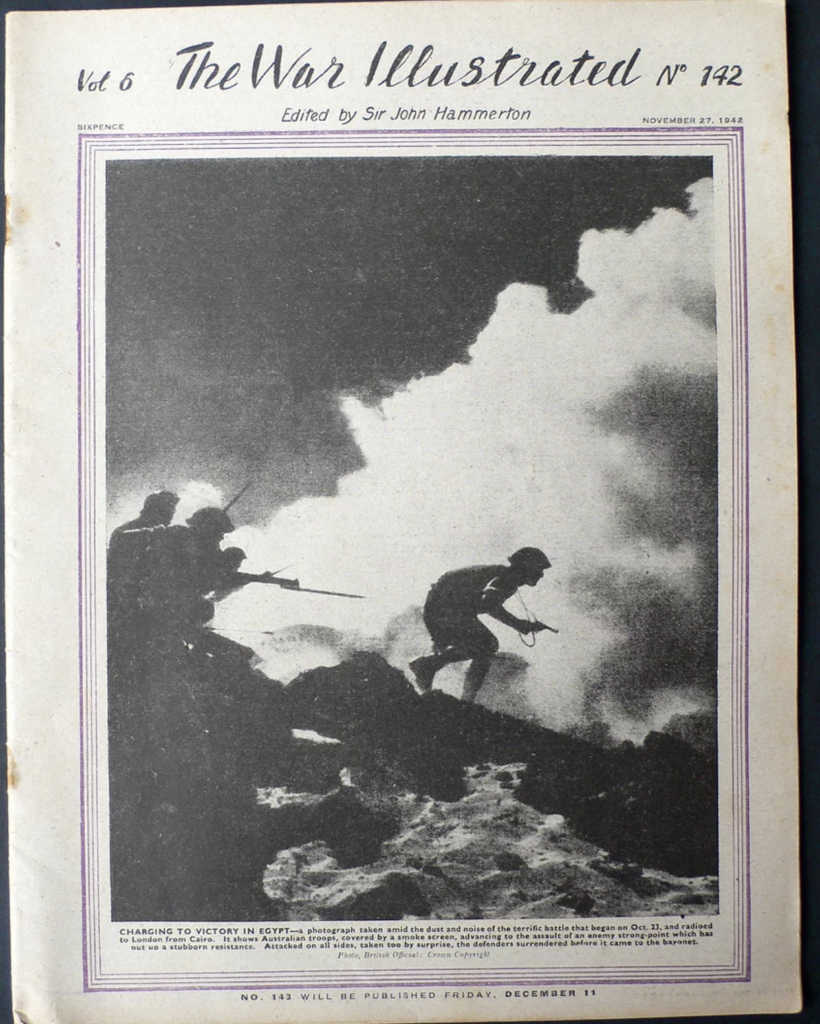

This photograph comes from a series by the British official photographer, Len Chetwyn, showing Australians at El Alamein. Chetwyn was a photographer with the British Ministry of information. The photograph was, however completely staged. Len Chetwyn and his AFPU team (Army Film and Photographic Unit) staged many similar scenarios between 1940 and 1943. Indeed many of the scenes would have indeed been possibly deadly to be present for real. However, even though some of the press images are captioned as posed, the onus is on the newspaper editor to include that information. Surely it will look better in the papers if the images are perceived to be real? Even with a caption I’m sure many would glance at the images without reading, or at least, taking the captions in fully. This particular image has been repeated so many times, and especially now with the internet provided an easy search tool, out of context it is taken as realistic, and it does look realistic! Im my circle of fellow 8th army fans this and many other of Chet’s images are posted online with comments such as ‘What brave men’ ‘I wonder if they survived?’ Now I am certainly not taking anything away from the true acts of bravery, of which some I read about are almost unbelievable.

One Victoria Cross was given posthumously to a 25 pound gunner, Adam Wakenshaw, who despite being badly wounded in several places including a head wound and his crew all dead around him, continued to fire on the German positions, despite taking enemy and fire indeed taking a one enemy gun position out. He was found dead against the breach, having managed to load a shell with one arm shot off still trying to fight. No photograph of him in action exists but just imagine how powerful that final image would be if it did and being undeniably genuine.

On lighter note…in following this line of research I now remember my father telling me during his time in the desert he witnessed an AFPU crew staging a scene where a group of soldiers were told to throw stones at a photograph of El Duce, Italian fascist leader, Mussolini that had supplied, while they filmed them. Not that this staging was of any major significance but it certainly proves a point.

Below is another of Chet’s photographs, colourised. Apparently showing a group of soldiers examining a German MP40 machine gun after presumably killing its owner, shown lying on the sand. Only the supposed German on the sand is wearing Britsh Army boots and long socks. Whilst its not inconceivable that a German might be wearing captured British boots (Although a poor choice as the German equivalent was far better designed more comfortable) and the Germans always had their socks rolled down. So this is a very nice image and certainly designed not to look posed, which it does very well with the off centre composition and casual poses.

Below is another Chet’s staged photographs, often mistaken in current media as a genuine image of the Battle of El Alamein.

Below is a example of Chetwyn’s images published without context giving an impression that the images were taken during real action.

Original photographs REFS:

The Australian War Memorial (s.d.) At: //www.awm.gov.au/collection/042070/ (Accessed 09/11/2020).

Bunyan, D. M. (s.d.) Len Chetwyn Australians approached the strong point. At: https://artblart.com/tag/len-chetwyn-australians-approached-the-strong-point/ (Accessed 09/11/2020).

‘Australians storm a strongpoint’. A posed portrait of Australian troops advancing during the Second Battle of El Alamein, 3 September 1942. E 18907 Part of WAR OFFICE SECOND WORLD WAR OFFICIAL COLLECTION Chetwyn Len (Sgt) No 1 Army Film & Photographic Unit (accessed 24th November 2020)

CLASSIC QUOTES

“The first casualty when war comes is truth”

Hiram Warren Johnson US Senator

“If it bleeds, it leads”

Unknown news person.

Iwo Jima Feb. 23, 1945

Joe Rosenthal took this iconic photo on Mount Suribachi on February 2nd 1945. It become a very influential image used was very comprehensively by American government in propaganda to maintain support for the campaign. This controversy stems around the fact that the US flag was raised on Mount Suribachi but general requested the flag be taken down and given to him as a trophy. Another flag was then raised again and this time it was photographed by Joe Rosenthal, indeed he won a pulitzer prize for it. (REF)

WW2 Red flag over the Reichstag May 2nd 1945

This is the second famous staged flag raising of the second world war. The Reichstag was it was actually stormed and the flag raised on the 30th April by Russian private Minin and a few comrades. Minin placed the red flag on the roof of the Reichstag that same evening. The iconic photograph below was taken two days afterwards (altered images)

A Russian army photographer named Yevgeny Khaldei went to Berlin with the intention of recreating photographer the famous Iowa Jima flag raising image by Joe Rosenthal. However he manipulated the image to add more smoke for drama in the scene. He used ‘dodging’ and ‘burning’ in the darkroom to exaggerate the solders shapes. He also retouched out multiple looted watches worn by the soldiers. Whilst the ‘dodging’ and ‘burning’ can be considered normal techniques that are simply enhancing what is already in the negative for artistic reasons, surely the adding and removing of elements are then obvious lies.

When Khaldei asked by German magazine Der Spiegel about the photograph and the manipulation, Khaldei said, “It is a good photograph and historically significant. Next question please.” (altered images)

ALTERED IMAGES (s.d.) At: http://www.alteredimagesbdc.org (Accessed 28/11/2020).

I can clearly see the necessity for the Russians to have their own iconic of victory over the German regime. The war between them had been a very long and bitter one with the Russian death toll across civilian army combatants around 11 million. Such hatred was held by the Russians for their foe that the final victory was surely to be represented in typical Russian victory style with their metaphorical and literal flag waving.

Vietnam

This is photographer, Eddie Adams’ incredibly famous Pulitzer Prize wining brutal image of South Vietnamese police chief, Brig. Gen. Nguyen Ngoc Loan, executing Vietcong fighter, Nguyen Van Lem, in Saigon on 1st February 1968, only two days after Vietcong and North Vietnamese forces launched their Tet offensive where North Vietnamese were on the streets of Saigon when the American public had been told the North Vietnamese were a defeated force the published photograph and story had a double shock value. Nguyen Ngoc Loan is recorded as saying this image ruined his life. Yet it is hard to decimate his later feeling from the very different circumstances of that time moment of time in the heat of conflict. Clearly no regard for the Geneva convention, but as Nguyen Van Lem was a combatant dressed in civilian clothing he was deemed a spy and hence the decision to execute. But and for me it is a big but, the general chose very deliberately not only do so in the open street but also to do this in front of a photographer. This is clearly not a staged photograph but to me it appears to have been created for the benefit of photographer and hence seeking the inherent publicity thereafter.

“Two people died in that photograph: the recipient of the bullet and Gen. Nguyen Ngoc Loan,” Adams wrote in the Time Magazine. “The general killed the Viet Cong; I killed the general with my camera.”

“Still photographs,” Adams wrote, “are the most powerful weapon in the world.”

CONCLUSION.

The driving force to produce the best image will always tempt the photographer to ‘push’ the ethics of photojournalism up to and maybe beyond its limits. In the ever increasing digital world we live in we must be, more than ever, be aware of the possibilities of twisted truths. My next blog will feature current Associated Press guidelines and their deficiency protect the truth in photojournalism.

Astor, M. (2018) ‘A Photo That Changed the Course of the Vietnam War (Published 2018)’ In: The New York Times 01/02/2018 At: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/01/world/asia/vietnam-execution-photo.html (Accessed 04/12/2020).